An attentive review of Brazilian artist Paulo Whitaker’s works on paper and canvas from the 1990s to 2023 will dispel any expectation of recognizable Brazilian tropes in his paintings – that is, the tell-tale bold, carnivalesque colours and bombastic all-over bold images. Whitaker avoids any hint of tropicalia in his studio practice. His sensibility doesn’t embrace irrational beauty, wild material desires, class pretention, the heroic artist’s journey or other flights of fantasy. Rather, his work delivers myriad combinations of evocative and interlocking painted parts/shapes/forms and diverse textures that speaks to an international modernism.

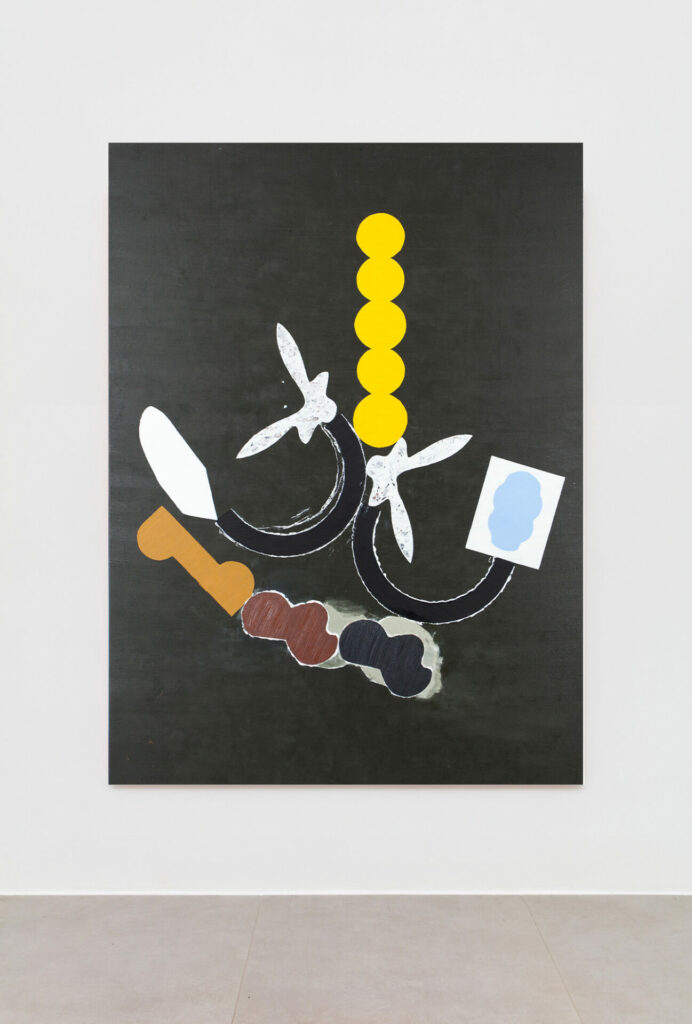

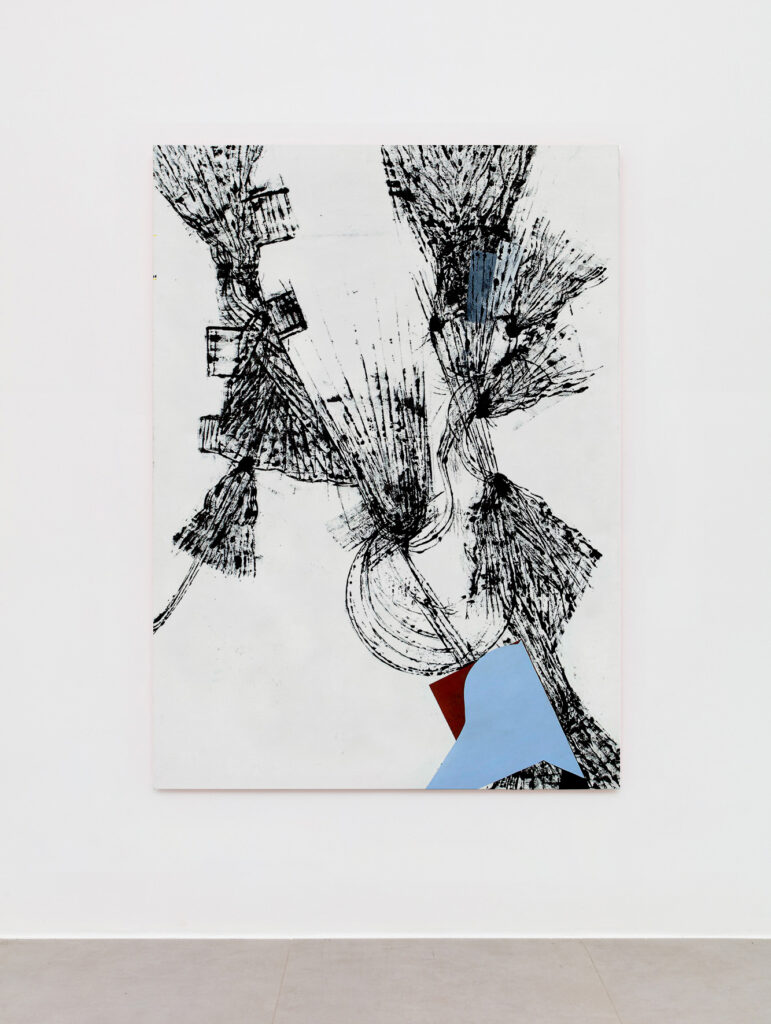

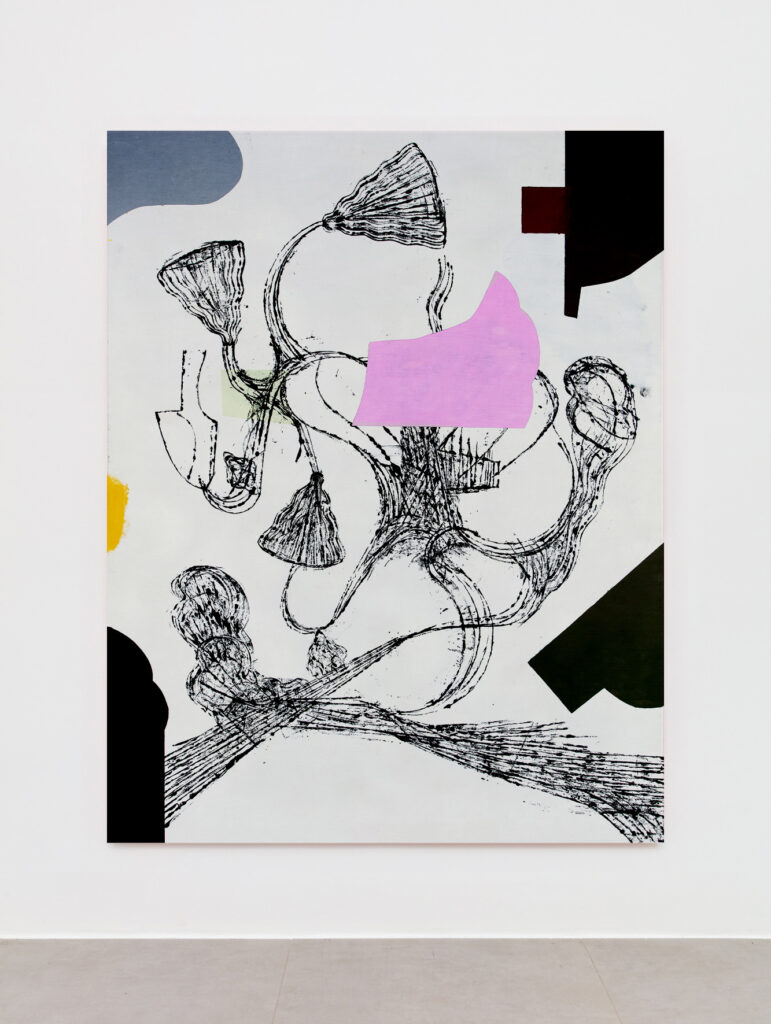

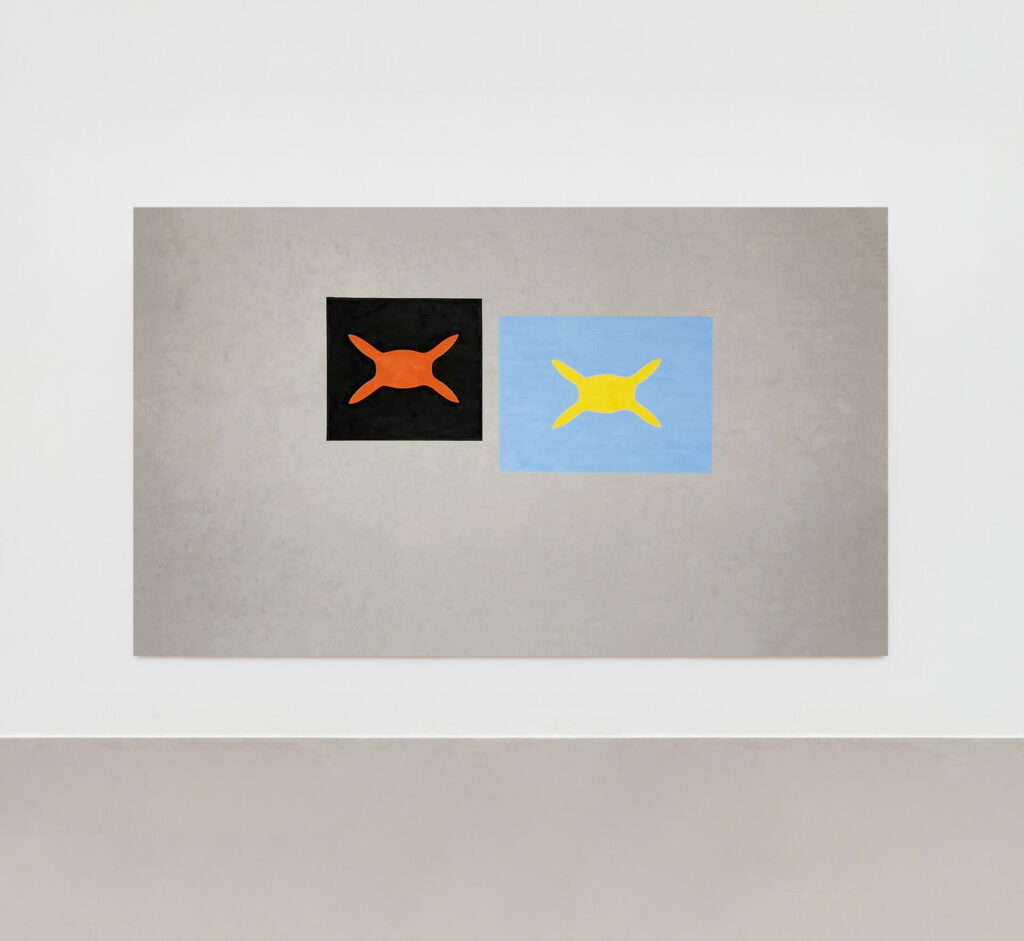

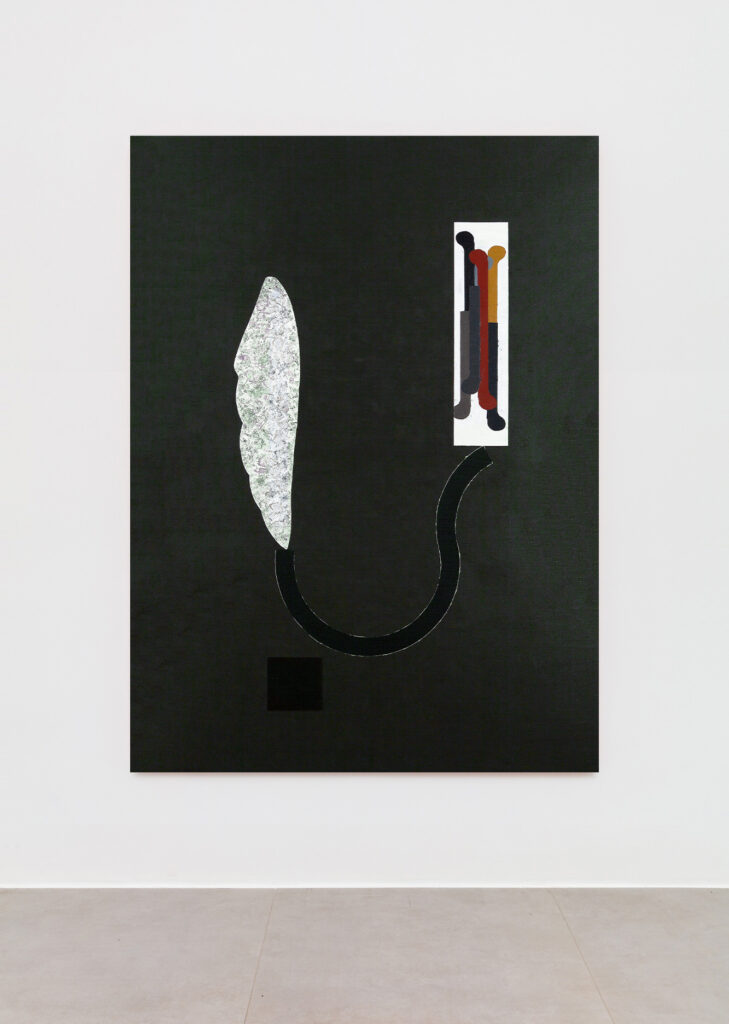

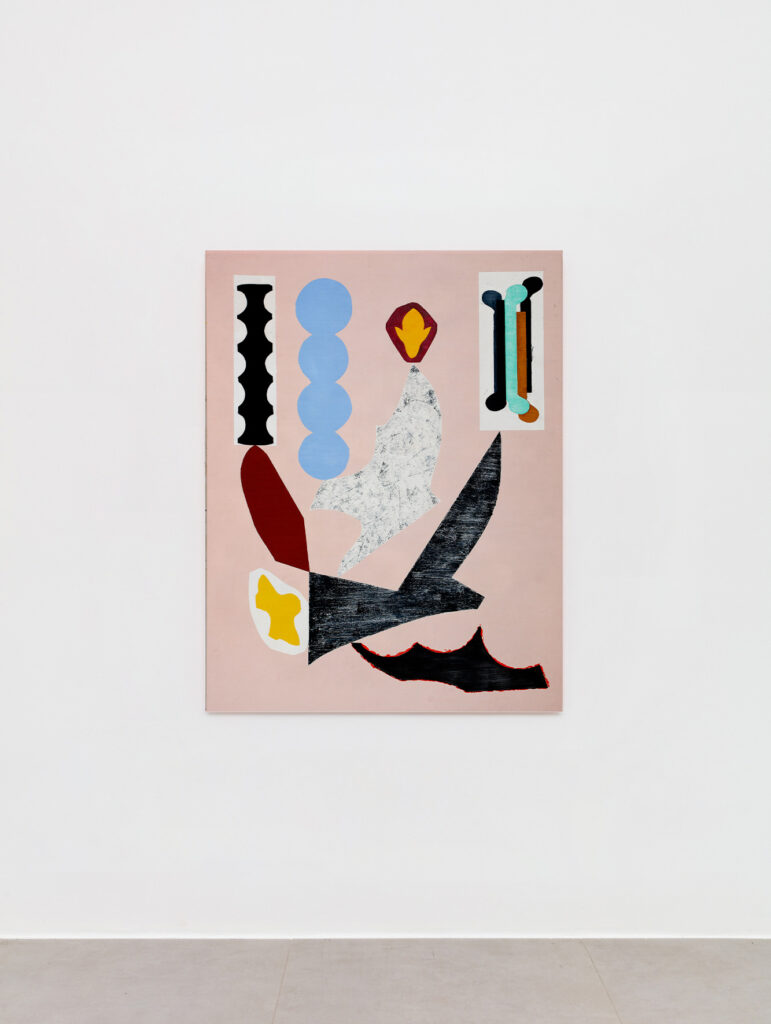

His visual footprint features a generally sombre colour palette and a style of mark-making in elegant shapes, linked in formal and often surprisingly awkward arrangements. The awkward stenciled blocks, flourishes on paper or minimalist outlines in black on canvas (or paper) is purposeful. Whitaker hints at a stylistic strategy that is expansive and inclusive. In conversation he admits, “…they (people) finish my paintings not only in their retinas, but in their heads, like editing a video on a computer, in the timeline mode, where they can add, subtract, reverse, slow motion, speed up, insert found footage, insert narration and so on.”

Whitaker generously gives viewers something as a late modernist take-away. He creates an open visual signature in the form of building blocks and he has the foresight to imagine how they might reassign colours, forms and language so invested in the history of painting.

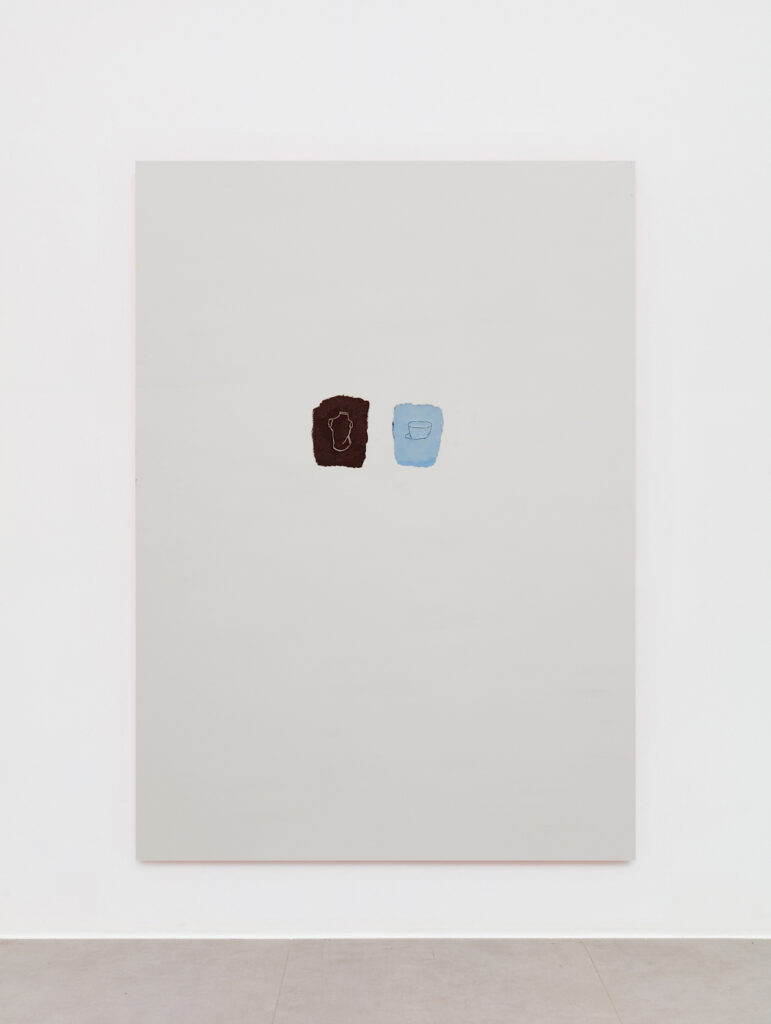

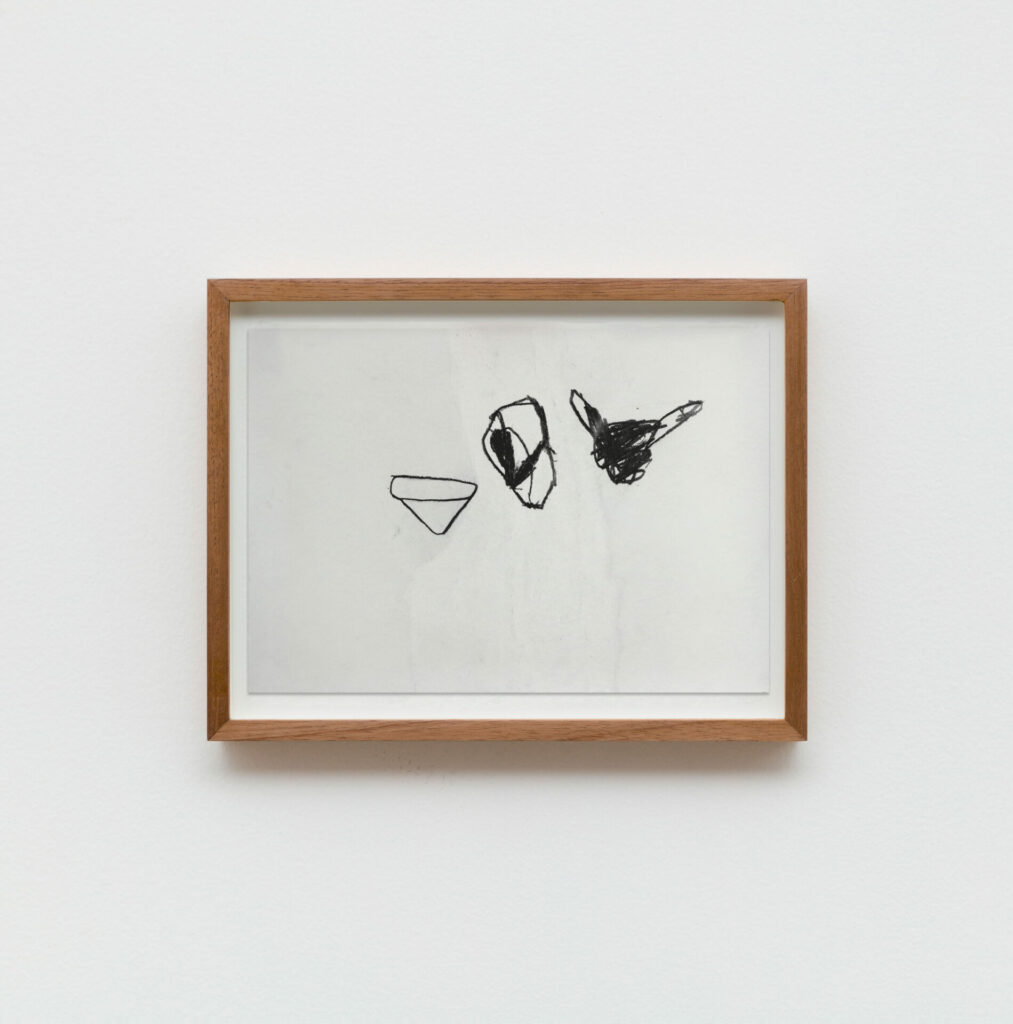

Each painting or drawing, regardless of its origins – either as “early work” (e.g., minimalist and ghostly graphite and charcoal drawings on a milky translucent wash from the 1990s) or what I call the current “throwback” period (when Whitaker freely integrates stylistic elements from various series made over the past 30 years) — offers a lesson in making. He insists on the freedom to revisit his stylistic paths without being bound to a chronology. He moves forward and backwards, with the freedom to move laterally.

If we study Whitaker’s various applications of fragmentation and repetition, it does not have so much to do with the drive to a modernist absolute of simplicity, certainty or negation of form. A painting’s capacity to elicit such absolutisms is there, in each work, but I think Whitaker’s play with the particularity of painting, hidden orders of the practice of mark-making and the changing context of uses is much more interesting to note. Early and current works share Whitaker’s highly experiential, relational exploration, always extending the parameters of modernist painting.

Each gesture, meaningless as it may appear over time, plays a recognizable role and often can be traced to aesthetic and stylistic influences from beyond his studio practice and current trends. Meaning and the meaningless form are produced relationally, in tandem, not in isolation. His dedicated studio production is part of something much grander and Whitaker is hyper conscious of it. His work integrates a compressed history of painting inclusive of image, colour, surface, process of making, language and even GPS location of origin.

Highly original in his placement of forms and colour, we nonetheless recognize his capacity to address the history of western painting as an exercise in a personal dialogue between artists, while being something of a modernist revolt against materialism and purposely located within a context for failure. Tellingly, his paintings enact a sense of amusement in their visual correspondence. Notice the peripheral presence of Donald Baechler, Eleanor Bond, Frank Stella, Tapies, or perhaps an unconscious wink at Miro’s curvilinear shapes. These are visual cues to a messaging as homage that all artists exchange over time and rely upon to propose a new and fresh context for their own work.

Whitaker suggests “art is more a thing based on accumulated experiences.” The past and present stylistic cues coalesce, often in tension, to inform meaning via abstract and figurative images, forms and sensibilities personified and woven into myth. But ultimately they act as bridges between historic traditions and convoluted meaning to find new ways to speak to us in the 21st century.

Wayne Baerwaldt