Julio Bittencourt was born in 1980 in Brazil and grew up between Sao Paulo and New York. His projects have been exhibited in galleries and museums in several countries and his work published in magazines such as Foam Magazine, GEO, TIME, The Wall Street Journal, Courrier International, C Photo, The Guardian, The New Yorker, Esquire, Financial Times, Los Angeles Times, and Leica World Magazine, among many others. He is the author of three books: “In a window of Prestes Maia 911 Building”, “Ramos” and “Dead Sea”.

It is six in the morning. The clock on the street announces it. Sixteenth of May, two thousand twenty-one, fifteen degrees. The news shouts that the country accounts for 435,823 deaths and 15,625,218 cases of COVID 19, according to the assessment of the press vehicle consortium – a partnership established between the main media groups in the country, which arose due to delays and data manipulation by the Ministry of Health in Brazil.

If three years ago the word “Fake” was among the most written and replicated, today it is used as a government strategy in news that are the envy of the most inventive screenwriters and that intend to draw attention away from the daily extermination of Brazilians; however, the fable is not a dilemma now. The photographs of the universe are fake or collages of thousands of invented color images. The calendar is a convention for counting time, just like the forms of representation of a territory on a relief map, a photograph or a globe.

Chloroquine, penis-shaped baby bottle, flat earth, Portuguese explorer, Treaty of Tordesillas, Princess Isabel. “History is fiction.” The “First Mass in Brazil” is fiction, both in the letter by Pero Vaz de Caminha and on the canvas by Victor Meirelles. The one who holds the power tells, writes, discloses, even dictates some mythical facts as historical. The faces on the money bills denounce: reality is socially constructed.

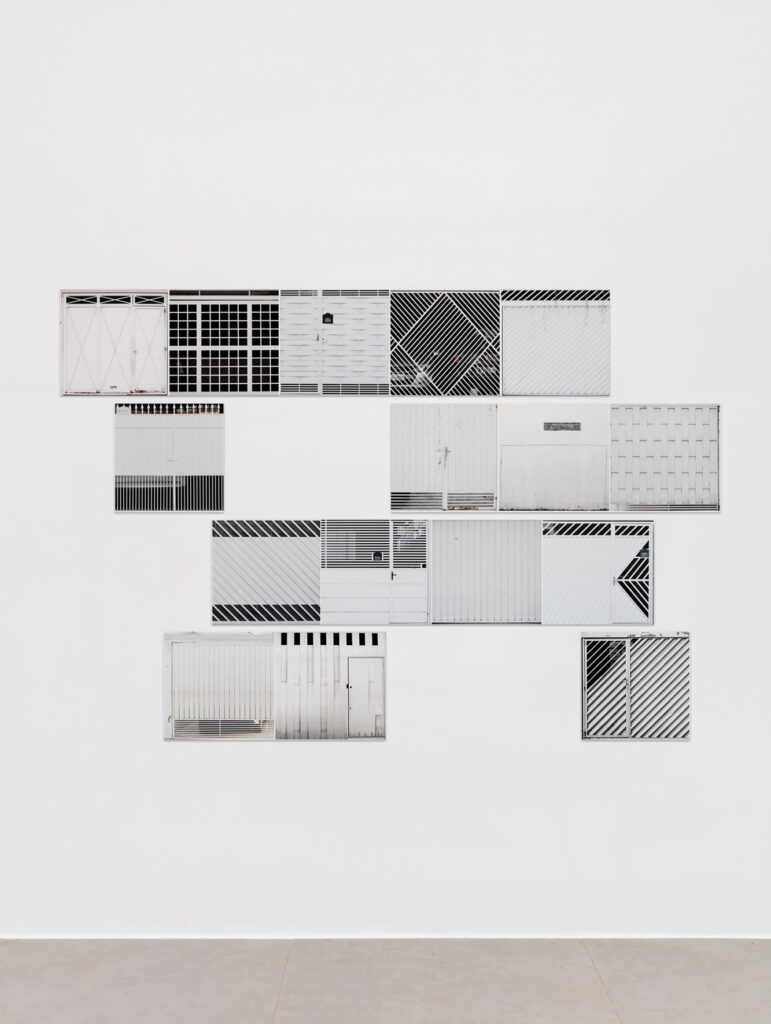

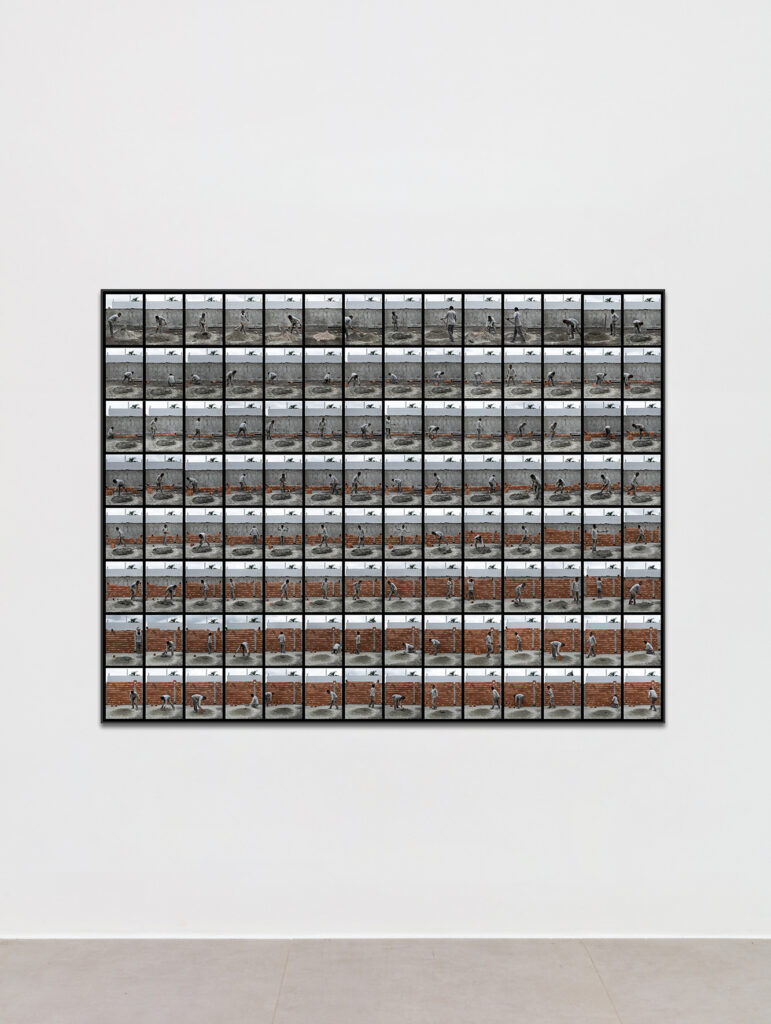

Abuse and manipulation of the truth in a despicable, reckless and sordid way omits, rejects and distorts the value of deception. Not of this politician’s hoax, but of reverie, illusion, poetry. Nonetheless, it insists, leaks through the cracks, crosses borders, folds, and makes the everyday object useless to give it new uses, other perspectives. To the photographs that are born with a documentary aura, the artist denies, exposes the verse, the negative, this ghost that is not the image but its passage.

“Amarelinha” no longer promises heaven, a paradise sold in installments in government slogans or entrances to neo-Pentecostal churches. First of all, character comes, or there is the risk of losing the turn.

Real FAKE does not intend to deceive the viewer, but, against all news lies, to honor poetic fantasy and show that, in fact, we can find in imagination and art a stimulus “to think of a more sensible world, to cultivate the chimera of being able to relieve -if not to destroy- the injustices that spread and the inequalities that weigh (or should weigh) like a stone in our conscience.”1

Paulo Kassab Jr.

1. Nuccio Ordine, “The Usefulness of the Useless.”